By Bill Lipsky–

On the evening of March 8, 1972, typical for San Francisco in the spring with its patchy fog and temperatures in the 50s, 41 people gathered at Glide Memorial Church on Ellis Street “to make plans for the first ever Gay Freedom Day Parade and Dance to be held in the City of Queens.” Less than three years after Stonewall, the last Sunday in June had become “Gay Freedom Day in America” and the meeting decided that “we San Franciscans should join in” the celebration.

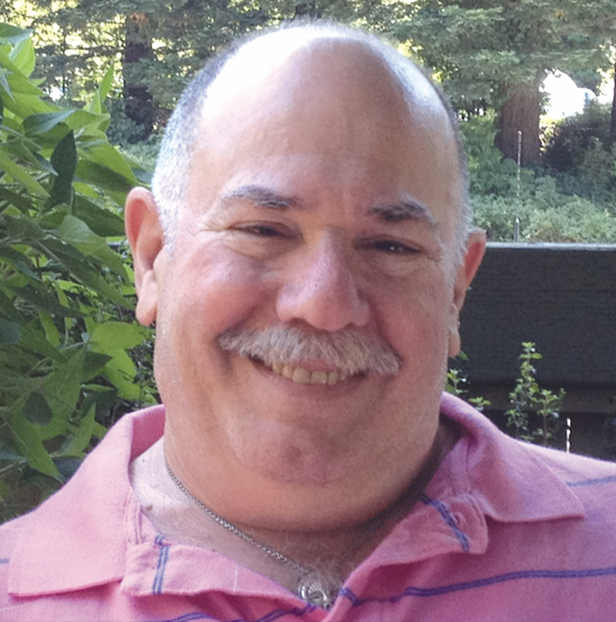

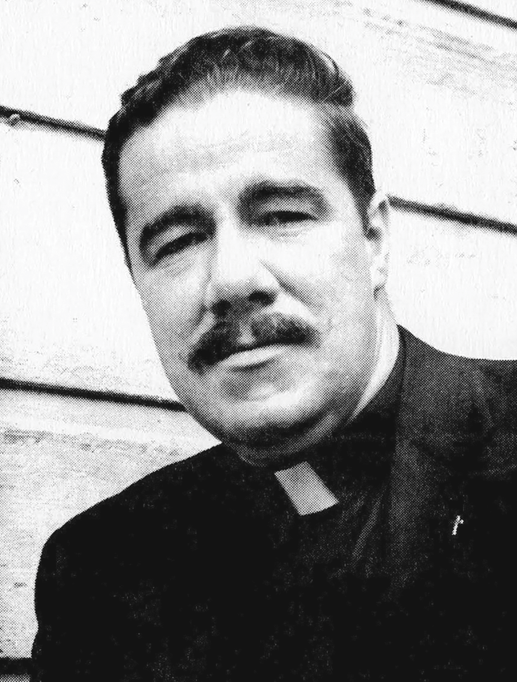

The meeting was co-chaired by the Reverends Ray Broshears (1935–1982) and Bob Humphries (1934–2002), who was one of the organizers of the Christopher Street West parades in Los Angeles in 1970 and 1971. Representatives from “every possible spectrum of the vast Gay Society of San Francisco” attended, including the Society for Individual Rights, the Metropolitan Community Church, the San Francisco Tavern Guild, and the Emmaus House, which operated a gay switchboard. There also were spokespeople for “the radical lesbians” and even “a biker.”

Those assembled voted 40–0 for having the parade; one representative stated “present.” The San Francisco chapter of the Gay Activists Alliance agreed to manage the project. Founded in 1970 by “Reverend Ray,” as he liked to be called, it was a “street people’s gay organization,” exclusively “dedicated to the eradication of all legal, political and economic oppression of homosexuals, the unconditional recognition of the basic rights of homosexuals, and the attainment of political power for homosexuals.”

One of San Francisco’s most vocal and controversial activists, Broshears was an early advocate for the marginalized communities of the Tenderloin, where “drag queens, old folk, hustlers, ex-cons, transsexuals, and queers,” he once declared, “see me as their last hope.” 1972 was a busy year for him. In addition to working on the parade, he co-founded the San Francisco Gay Crusader and opened the Helping Hands Community Center at 255 Turk Street to minister to those in need.

Broshears and Humphries became co-chairs of the first parade committee, which included Gary, “the Wicked Witch of the Golden West,” and H.L. Perry, “one of the city’s unsung gay heroes,” who at the same time was co-founding the Grand Ducal Council of San Francisco, where he reigned as Grand Duchess I from 1973 until 1974. While in office he created the Royal Bunny Contest, held in Golden Gate Park; organized an annual food drive; and opened Atlantis House, a half-way house for gay ex-cons.

It was officially named The Christopher Street West-SF Parade, and the newly formed group immediately adopted a non-exclusionary policy, affirming that everyone in the community was welcome to participate. The organizers recognized from the beginning that, for some people, the parade would be controversial, so they willingly listened to different points of view. “If the parade is not to your liking, for any of a variety of reasons,” they stated in an early announcement, “then come to our meetings and discuss the difficulties, present alternatives.”

Ultimately, they made clear, “This is a celebration for the Community. It is a joyous outpouring of our gayness for all the world to see, in whatever form we feel that gayness takes … . The only people who will be excluded will be the people who exclude themselves.” A few organizations declined to be involved when their requests to keep drag queens and muscle-boys from marching were denied. The committee refused to deny any expression of gayness.

The 1972 parade route took participants from Montgomery and Pine down Montgomery to Post, up Post to Polk, then along Polk to the Civic Center, where they gathered in celebration for the rest of the afternoon. Parade entries represented everyone from gay theatrical groups to the Alice B. Toklas Memorial Democratic Club, the oldest queer Democratic club in the country, founded the year before. In the evening, merrymakers partied at a dance at Playland, the city’s amusement park on the Great Highway.

The parade was not without its controversies. Perry attended the festivities in high drag, then not to everybody’s liking, and Broshears, according to Humphries, “outdid himself by punching a gay woman and destroying her sign which said ‘Off Prick Power.’” (Apparently, she was objecting to the fact that the organization’s officers that first year were all white men.) She later “rounded up some of her friends and gave Ray a few gay knocks after the parade on the steps of City Hall.”

Neither of the first two grand marshals were San Franciscans. Morris Kight (1919–2003) lived in Southern California. A long-time human rights activist, he was instrumental in organizing 1970’s Christopher Street West Parade in Los Angeles. During an era when the American Psychiatric Association diagnosed homosexuality as a mental disorder, he told celebrants that they “should be more than just proud—they should be ecstatic, for theirs is a natural, evolutionary heritage that at long last is gaining recognition in its natural, beautiful light.”

Grand Marshal Freda Smith (1935–2019) lived in Sacramento. Hers was a life of love, faith, and activism. She knew who she was at an early age, but did not fully accept her sexuality until she came to understand “that God did not want to change her, but wanted to use her passion as she was, to help those like her who were struggling.” She then decided to “devote her full time and talents to the struggle for Human Liberation,” especially “the struggle for Gay and Women’s Liberation.”

In 1972, Smith became the first woman to be ordained a minister of the Metropolitan Community Church, serving initially as Assistant Pastor and then as Pastor of the Sacramento MCC until 2005, when she retired. She also co-chaired the California Committee for Sexual Law Reform, where she worked tirelessly to overturn the statutes that criminalized same-sex intimacy in California. She demonstrated, spoke out about, and lobbied for passage of the Consenting Adults Bill, sponsored by San Francisco Assemblyman Willie Brown, which was finally signed into law in 1975.

The 1972 parade attracted some 2,000 participants and 15,000 spectators, numbers that have increased exponentially every year since. What accounted for this success? As Reverend Bob wrote on the parade’s 10th anniversary, the parade “is an exercise of Gay community strength, unity, clout, foolishness, diversity, and outrageousness. The parade is the Gay community for all the world to see, and if it doesn’t like what it sees, it can damn well look the other way, because we are beautiful, we are real, and we are not going away!”

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “LGBTQ+ Trailblazers of San Francisco” (2023) and “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Published on June 26, 2025

Recent Comments