By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

Had he wanted the attention, Michael Dillon could have become one of the world’s most famous physicians—not for developing a new medical procedure or discovering an unknown scientific principle, but for being the first person to use plastic surgery to change his outward physical appearance as a woman to correspond with his self-knowledge and emotional awareness as a man. Instead, he sought anonymity and the right to live his life as himself, without any glaring notoriety or mocking curiosity seekers.

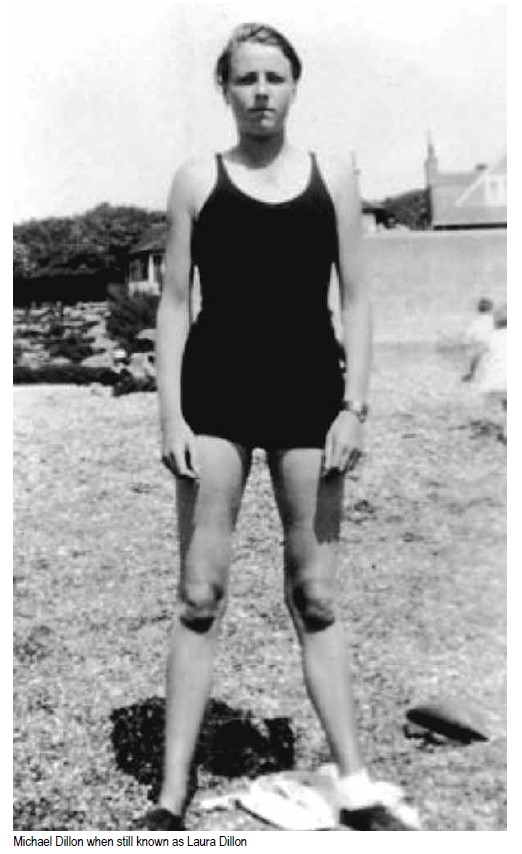

The second child of the heir to the baronetcy of Lismullen, Ireland, and christened Laura Maud, Dillon was born 1915. Growing up, he sensed that he was “a man trapped in a woman’s body,” but in the early decades of the 20th century, terms like transsexual and transgender did not exist; there was no information that explained his feelings, no professional support or role models. Until he graduated from St. Anne’s College at Oxford University in 1938, Dillon essentially was alone in his search to become himself.

Eventually Dillon found a surgeon at the Royal Infirmary in Bristol who both understood his situation and supported his objectives. Knowing that a diagnosis of hypospadias had enabled several categorized “female” patients to revise their birth certificates to state they actually were male, he wrote out a note for Dillon. The clerk at the local Labor Exchange, also sympathetic, accepted the information and changed the gender from female to male on his registry documents. Dillon now had official papers stating he was a man.

In 1943, Dillon met with the pioneering plastic surgeon Harold Gillies, possibly the only person in the United Kingdom who truly could help him. Gillies saw Dillon’s situation the same way as he did: he was a man with a woman’s body. Gillies agreed to work with him, but not until the war ended. In the meantime, inspired by the man and his work, Dillon decided to become a physician himself.

His academic records, however, were an obstacle—not because of his grades, but because they identified him as Laura Maud Dillon and showed he had attended an all-women’s college. The problem was solved, amazingly, when a former tutor at Oxford convinced the university registrar first to replace his birth name with L. M. Dillon on all his documents, and then to change his alma mater to Brasenose College, an all-men’s school. Dillon then applied to Trinity College, Dublin, where he received his medical degree in 1951.

Officially diagnosed with acute hypospadias to hide the fact that he was undergoing sex-reassignment surgery, Dillon endured at least thirteen operations between 1946 and 1949. They made up Britain’s first true gender alignment procedures, which at the time almost no one believed were possible and many believed were illegal. A few years later, Dillon became the physician on board a merchant ship. At last, he felt welcomed as an equal into the company of men, who asked no questions about his life history.

Dillon continued to fret about his years as Laura becoming known, but by now he had found many friends who, even when they learned more about Dillon, only saw the man in front of them. So, in 1953—the same year that Christine Jorgensen made headlines around the world—he contacted the editor of Debrett’s Peerage, a reference book that listed the well-born of the United Kingdom and Ireland, to revise his family’s entry.

After presenting his revised birth certificate and other documents and then explaining his history, Dillon asked that the entry about his family include him as a man, not, as it did currently, as a woman. The editor not only agreed, but he also stated that he would support Dillon as the legal heir to the baronetcy. “I have always been of the opinion,” he stated later, “that a person has all rights and privileges of the sex that is, at a given moment, recognized.”

Dillon believed that Burke’s Peerage, a similar publication by a different firm, also would change its information about him, but it continued to list him as Laura. No one noticed the discrepancy between the two reference books until 1958. Then newspaper after newspaper reported the story. Although his ship’s captain and crew protected him from reporters when they were in port, Dillon chose to reestablish his anonymity by escaping to India, where he embraced Buddhism. He died there in 1962, 47 years old.

Dillon wrote two books about the knowledge he had acquired from his journey to personal understanding. Self, published in 1946, was one of the earliest works to present a classification system for gender identity and sexual desire. Dillon argued that true gender identity had nothing to do with outward physical appearance. A core human characteristic, the sense of being male or female, he wrote, was the result of “psychological build.” The only way to determine an individual’s true gender? Ask the individual.

Why, he wondered, should transgender people be forced to make their minds fit their bodies when, in fact, they needed their bodies to “be made to fit [their] mind.” It was the body, not the mind, that did not fit. Give patients the body they wanted, he asserted. Give them their options and let them decide. Patients, not doctors, should have the final say about who they are and how they look. Seventy-five years ago, all this was revolutionary thinking.

Dillon’s second book, Out of the Ordinary, his autobiography, was completed in 1962, the year he died, but remained unpublished until 2017. In many ways the story of the anxieties, burdens, and barriers faced by transgender people during his lifetime, it also was something more: the account of an individual continuously seeking to discover and understand his true nature—physical, emotional, and spiritual—and the “fierce will,” as the historian Susan Stryker wrote, “to make real for others the inner reality that trans people experience of themselves.”

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Published on January 14, 2021

Recent Comments