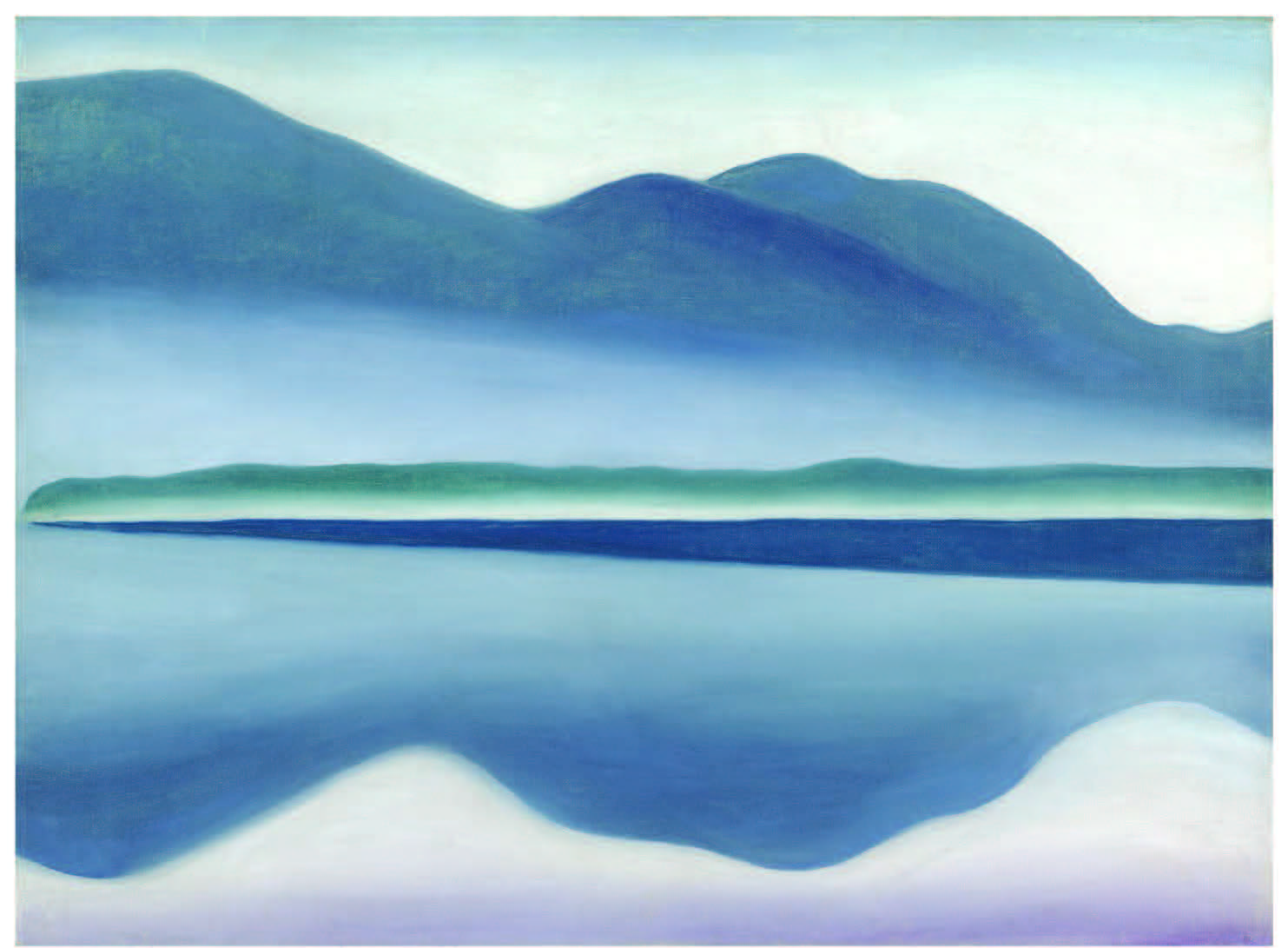

Georgia O’Keeffe, Lake George, 1922. Oil on canvas. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, gift of Charlotte Mack. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

American artist Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) seemed to have a love-hate relationship with feminism. She once exclaimed, “I am not a woman painter!” and yet the pro-suffrage National Women’s Party member also said, “I believe in women making their own living. It will be nice when women have equal opportunities and status with men so that it is taken as a matter of course.”

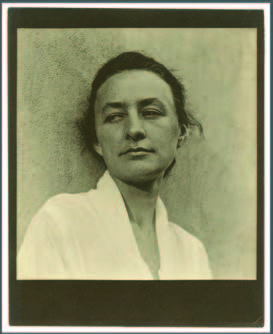

Paul Strand, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1918. Photograph, platinum print. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Copyright © Aperture Foundation, Inc., PaulStrand Archive. Photo: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution / Art Resource, NY

Numerous books claim that O’Keeffe was bisexual, but this too falls into murky historical waters. What is clear is that many LGBT supporters and individuals—especially lesbians—relate to her art and legacy. Artist Judy Chicago, a longtime champion of gay rights who embraced feminism, included O’Keeffe in her own seminal work, “The Dinner Party,” which presents a veritable pantheon of women artists, poets, novelists, rulers and goddesses.

Flowers, which O’Keeffe beautifully and unforgettably painted, can themselves be bisexual. Most large, showy flowers, such as lilies and roses, are bisexual, possessing both male and female reproductive structures. Artists infuse their works with their own particular energy and life’s experiences, so it’s fascinating to experience O’Keeffe’s tremendous power through something as seemingly soft and non-threatening as a flower, a lake or another aspect of nature. The images, for us, explode from their surfaces with captivating sensual energy.

But perhaps you perceive something else in them. Whatever your personal response is, the images likely will lure you in like an ephemeral flower attracting desirous honeybees. American artist Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) seemed to have a love-hate relationship with feminism. She once exclaimed, “I am not a woman painter!” and yet the pro-suffrage National Women’s Party member also said, “I believe in women making their own living. It will be nice when women have equal opportunities and status with men so that it is taken as a matter of course.”

On behalf of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, it gives me great pleasure to introduce the special exhibition Modern Nature: Georgia O’Keeffe and Lake George, on view at the de Young in Golden Gate Park through May 11, 2014.

On behalf of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, it gives me great pleasure to introduce the special exhibition Modern Nature: Georgia O’Keeffe and Lake George, on view at the de Young in Golden Gate Park through May 11, 2014.

Georgia O’Keeffe is one of the most renowned—and most loved—American artists, and many associate her with the mountains, deserts, and expansive skies of New Mexico, where she lived and worked during the second half of her life. In the coming months, however, visitors to the de Young will have an opportunity to explore an earlier and equally significant period of the artist’s career, the one during which Georgia O’Keeffe became the artist we admire today.

From 1918 until the early 1930s, O’Keeffe spent part of each year in upstate New York, at the Lake George family home of Alfred Stieglitz, the pioneering photographer and art dealer whom she married in 1924. From spring to fall, O’Keeffe resided on the property in the Adirondack mountains for extended periods of time, experiencing the spectacular chromatic effects of the changing seasons and exploring its shorelines, hillsides, and panoramic vistas.

At Lake George, O’Keeffe developed the subjects and themes that are considered essential to the evolution of her signature style of modernism. Spending time in nature gave the artist the experience of a different way of looking: close attention to detail paired with simplification of forms led her to depict landscapes, flowers, fruits, trees, leaves, and architecture in new ways. She strove to capture the spirit of the place without losing the connection to the specific things depicted. This innovative approach informed her work during the Lake George period, and laid the foundation for subsequent work in New Mexico.

It is gratifying to host this pioneering survey of Georgia O’Keeffe’s Lake George–period works, as it also offers visitors greater understanding of one of the Museums’ most important American paintings, Petunias (1925). Featured in the exhibition, this composition is a highlight of our American modernist collection and is a true favorite during our annual Bouquets to Art celebration.

This year, we look forward to welcoming more than 50,000 visitors to Bouquets to Art, for which floral designers craft inspired arrangements that are paired with works of art in our galleries. I trust that you will enjoy this special display, which will be on view for the limited time of March 18 through 23.

I hope you will join us at the de Young to explore the extraordinary art and life of Georgia O’Keeffe, a great American modernist, and to celebrate the beauty of nature and art in Bouquets to Art.

Colin B. Bailey

Director of Museums

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Recent Comments