By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

During the early years of the 20th century, no one could have imagined that an openly lesbian woman, writing romantic stories about intense emotional relationships between young women in a deeply patriarchal society, would become one of Japan’s most prolific, successful, and influential writers. A pioneer of sh?jo sh?setsu (girls’ fiction), Nobuko Yoshiya (1896–1973) published her first sketches while still in her teens, became her country’s highest-paid author less than 20 years later, and is still an important inspiration for modern sh?jo manga (graphic novels for girls).

Nobuko’s middle-class, culturally conservative parents trained her for the “good wife, wise mother” role expected of women in Meiji era Japan. A lecture she attended by author and educator Nitobe Inazō during her first year at Tochigi Girls’ Higher School, however, changed all that. “I believe,” he said, “you all should be a good person before you become a good wife or mother.” His ideas inspired her to discover who she was as an individual, as a woman, and as a creative mind.

The years between the World Wars provided her with an opportunity to do just that. She moved to Tokyo in 1915, embraced Japan’s emerging “modern girl, modern boy” movement, with its “Western” ideas and fashions, and began to live as she chose, not as society told her she must. She became one of the first women in the country to cut her hair short in the “Western style” and to wear non-traditional, often androgynous clothes. She owned a car, which she drove herself, designed her own house, and even played golf.

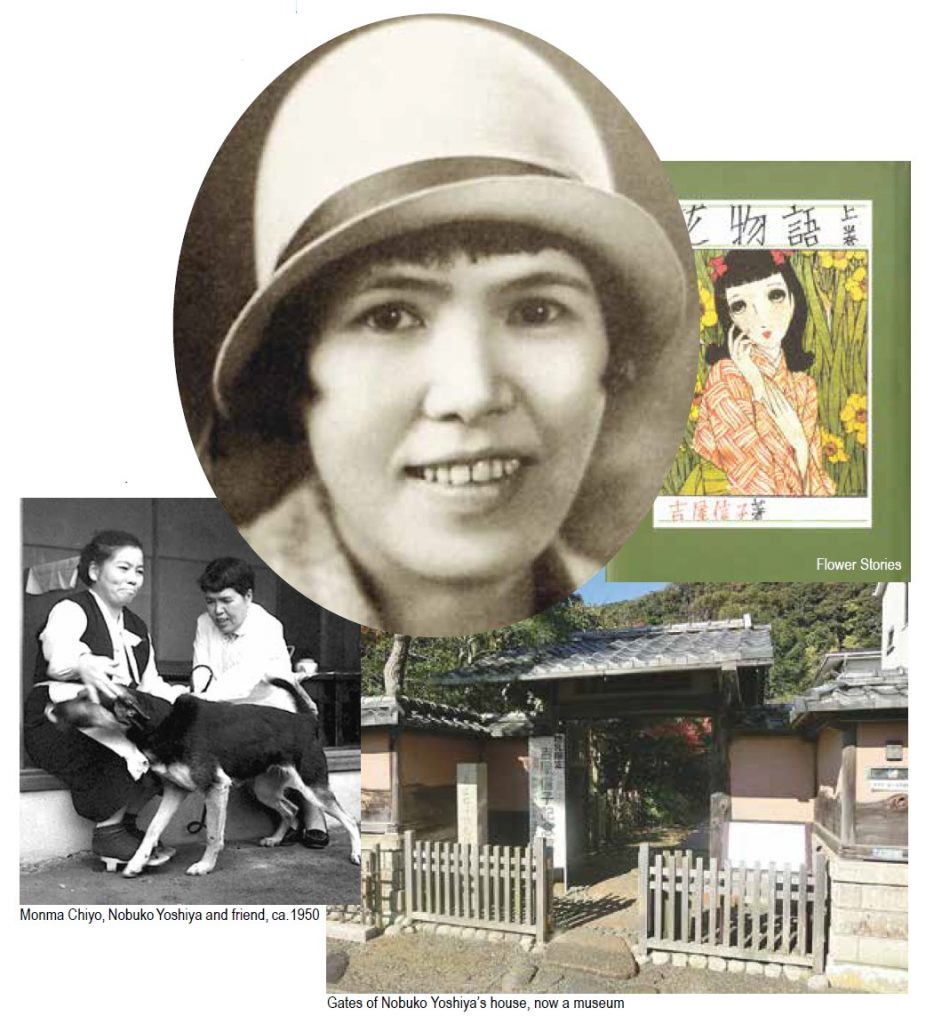

Nobuko’s first important work was Hana monogatari (Flower Stories), a collection of 52 sketches of female friendships that appeared serially between 1916 and 1924 in Sh?jo Sekai (Girls’ World), one of Japan’s earliest magazines for young women. Each story focuses on the feelings of affection, admiration, or adoration of two women for each other: a teacher and a student; a mother and a daughter; two adolescents. Although critics ignored it, the schoolgirls for which it was written did not.

In stories like “Yellow Rose,” recently translated into English by Sarah Frederick, Nobuko described how two young women could develop deep emotional bonds with each other, and she shared her concerns about how social convention then destroyed their relationship. Katsuragi Misao, 22 years old, has accepted a teaching position at an all-girls school, “a thousand miles from Tokyo,” to avoid getting married. On the train she meets Urakami Reiko, a student entering her final year at the same school.

After reaching their destination, teacher and student become great friends and deep feelings of affection develop between them. Their endearment remains platonic always, although, as Kathryn Hemmann has pointed out, Nobuko allows readers to fill in any suggestive gaps in the text with their imaginations. They make plans to visit the U.S. together after Urakami graduates, but her mother expects her to enter an arranged marriage immediately. As Katsuragi boards the ship to America alone, she “abandons herself to her grief.”

Here was something new and different: a story for girls that spoke directly to them and understood the feelings they were experiencing, but might not yet fully understand. It did not prepare them for a traditional role, but told them that, despite all the social pressures to conform, there were other possibilities, filled with beauty, affection, and the opportunity to express their true selves. What happens to the women becomes much less important than the women themselves and their tenderness for each other.

Nobuko acknowledges the internal emotional conflicts these young women face. “The sadness of those who love their own sex and therefore cannot live their lives in the form of a conventional marriage is redoubled by the chagrin of parents—for whom marriage represents the sole pinnacle of womanly achievement—and the opprobrium and scorn of everyone else.” There is hope, however, given “the utopian possibility of a space for these two girls’ love, even when there is no space other than in the depths of their own hearts.”

Nobuko only occasionally wrote explicitly about a romance between two women, but she did so in Yaneura no nishojo (Two Virgins in the Attic), published in 1919. Based upon her affair with Kikuchi Yukie when both women lived at the Tokyo YWCA, it tells the story of two students, Akiko and Tamaki, whose longing for each other finally ends in a kiss and, unique to books about women for many years, a happy ending where they decide to live together as a couple.

Nobuko was already a successful author when she met Monma Chiyo, a 23-year-old mathematics teacher, at the beginning of 1923. Their loving relationship and collaborative partnership lasted for more than five decades. Perhaps Nobuko expressed her feelings best in her diary. “Chiyo,” she wrote, “I give thanks to fate which gave this person to me.” Unlike many people of her generation, in whatever country they lived, Nobuko was never guarded or secretive about her personal life with Monma.

Throughout their years together, the two women expressed their ongoing affection for each other openly, honestly, and lovingly. When Nobuko passed, with Monma holding her hand, her life partner said of her, “Even in her old age, Ms. Yoshiya remained in pursuit of the sweet fragrance of her girlhood dreams. Perhaps that is why I was attracted to her.” What were those “girlhood dreams?” As Nobuko herself said, “There is nothing shameful about loving someone or about being loved by someone.”

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Published on December 2, 2021

Recent Comments