By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

In 2021 San Francisco made history and once again set an example for communities everywhere when Mayor London Breed declared August to be Transgender History Month in the city. Following efforts by Jupiter Peraza and other activists, her proclamation not only celebrated the 55th anniversary of the Compton’s Cafeteria Riot, but also the many trans people who have lived here and made contributions to the fabric of place that has been their home at least since the Gold Rush.

“San Francisco is a city that possesses so much trans history,” Peraza explained during the annual celebration in 2022. “I want trans history month to be an opportunity in which we truly celebrate with joy and happiness, the icons and the legends that came before us. I want to also let every trans person know that they are indeed special. They are incredibly valuable, and that this place, this world, this life would not be the same without them.”

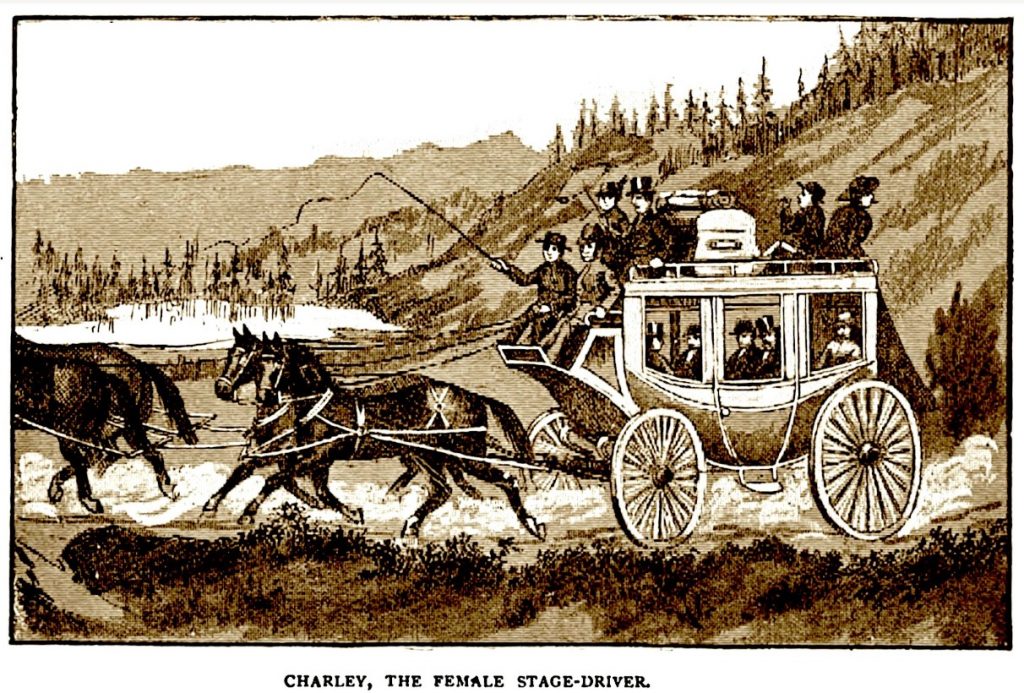

Among those icons and legends is Charley Parkhurst (1812–1879), for some 15 years one of the most celebrated stagecoach drivers in California. Described as having a “stout, compact figure, sun browned skin, and beardless face with bluish-gray eyes,” Charley was “the boss of the road” on the routes from Sacramento to Placerville, Oakland to San Jose, and San Juan Bautista to Santa Cruz. Not until his death did anybody know that “Cockeyed Charley” had been identified female at birth, the only such stager in state history.

Of course, as a woman Charley never would have been hired by a stage line or for any of the work he did after retiring as a driver. Always highly regarded, “He was known as one of the most skillful and powerful of choppers and lumbermen,” The San Francisco Call remembered in 1880, and “his services were eagerly sought for, and always commanded the highest wages, often as much as $125 a month, plus room and board.”

The state’s “crack whip” lived as a man for his entire adult life. He even registered to vote in 1867, more than 50 years before women’s suffrage was granted by the 19th amendment; “Parkhurst, Charles, 55, New Hampshire, farmer, Soquel,” reads his entry in the official ledger. If he voted—no record has yet been found—then he also was the first anatomically female citizen to cast a ballot in a presidential election in California.

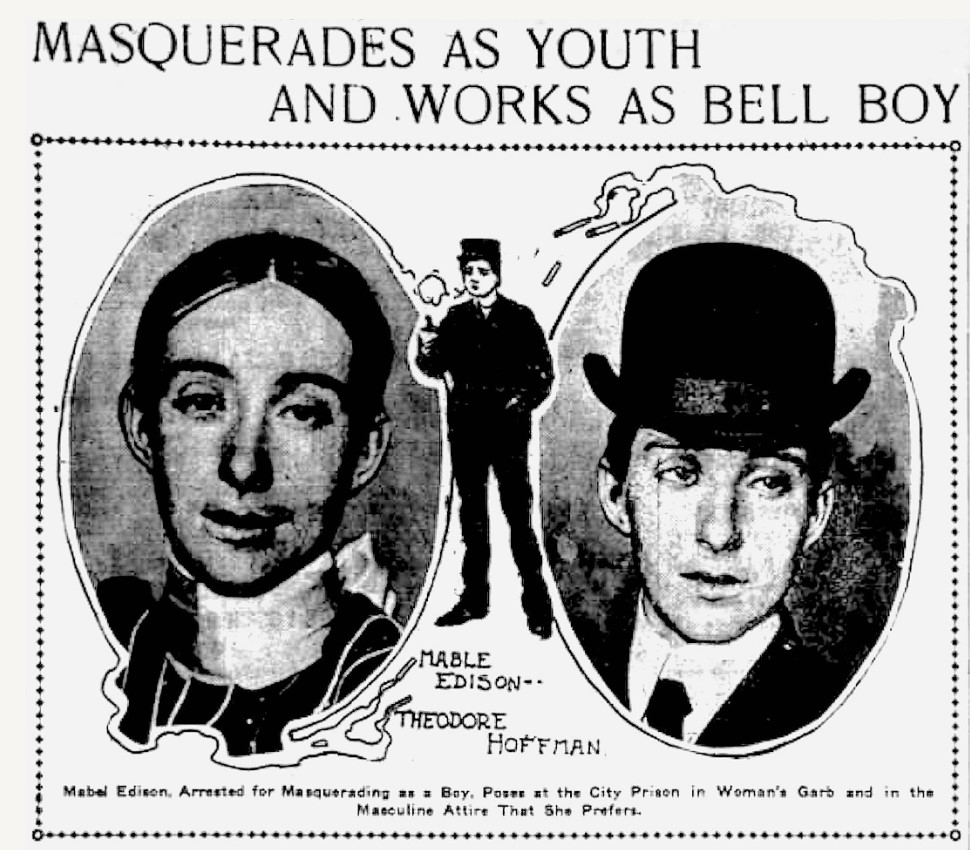

Where Charley kept his birth gender a secret for his entire life, Theodore Hoffman did not. Perhaps the first San Franciscan to be publicly revealed as someone we would identify as transgender, Hoffman, née Mabel Edison, was “only 22 years of age” when he was arrested for “impersonating a man” in 1902. “I always wanted to be a boy,” he told The San Francisco Examiner. “I cannot remember the time when I did not detest petticoats. My hatred for them was what finally landed me in jail in San Francisco.”

Theodore knew who he was. “All the arresting and all the preaching in the world can’t change a person’s nature. It is my nature to hate skirts. As for the law that compels men and women to wear different styles of clothing, I do not propose to obey it … . This is supposed to be a free country, and yet they arrest a person who is quietly minding his own business. I say ‘his’ business because I never think of myself as a woman at all.”

He had dressed in male attire before. “I can remember my mother telling me that when I was a year and a half old, I always wanted to wear my little brother’s clothes,” The San Francisco Chronicle reported. “With boy’s clothes, boy’s voice and boy’s manners came a boy’s way of thinking, and it seemed to me that I was in my natural element.” Finally, “When I was 21, I decided to become a man—I was of age, so why not?”

Hoffman was only released from police custody after agreeing “to begin life over again under proper conditions and with a different name” as a woman. “The officers need not think that they have cured me of my liking for trousers, nor the folks who have preached to me about what they term my ‘bold behavior’ in masquerading as a man.” In fact, “I have my boy’s clothes handy … and I shall have the pleasure of outwitting the officers in the future.”

Unlike Hoffman, Felicia Elizondo struggled to understand who she was. Born in San Angelo, Texas on July 23, 1946, she was identified at birth as male and baptized as Felipe. She soon realized she was different from the children around her, but did not yet understand what exactly that meant for her. Despite all the prejudice, inaccuracy, and obstacles put in her way, however, she came not only to realize her true self, but also to find the strength and the courage to live an authentic life.

“I thought I was gay, but I wasn’t,” she later said. At age 15 or 16, living in San Jose, she began seeing an older man who one day took her to San Francisco, where they visited the Tenderloin. “I noticed that there was a lot of people like me,” she later told Zachary Drucker of Vice News. She and a friend began to “play hooky from school and come into the Tenderloin on a Greyhound,” where Compton’s Cafeteria became “the center of the universe for us.”

By the time she graduated high school, Elizondo had decided she did not want to be gay any longer. What she wanted instead was “to be normal,” not yet understanding what normal was for her. She concluded that if it meant being “straight,” then military service would be her deliverance. It was not. After serving in Vietnam for six months with the Navy, she told her commanding officer that she was gay and was discharged. She then returned to the Bay Area, still unclear about her real identity.

The pieces of the puzzle of who she was came together not long after while living in Chicago. “What changed my life was when I went to see the movie, The Christine Jorgensen Story,” the so-called biography of the most famous transgender woman of her time, made by the gay director Irving Rapper. “I finally realized that this is who I am. I didn’t know how I was going to get there, but where there is a will, there is a way.”

Elizondo found a way. In 1972 she began living full-time as a woman. Two years later, when she completed her surgery, she finally was her true self. After retiring, she became an advocate for the transgender community, especially trans women of color, who were often confronted with both racism and transphobia. Remembering the past was important to her, too. “Please don’t forget all who came before you,” she wrote in 2018, three years before she died. “You have to know where you have been to know where you are going.”

Her words are more imperative today than ever. As Pau Crego, Executive Director of the Office of Transgender Initiatives, said at the beginning of this year’s Transgender History Month in San Francisco, “It is especially vital now … to remember and celebrate the trans community’s history, at a time when there are over five hundred anti-trans bills being proposed nation-wide. San Francisco’s history is intertwined with trans liberation, and upholding dignity, safety, and well-being for our transgender residents is an inherent part of our legacy.”

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Published on August 10, 2023

Recent Comments